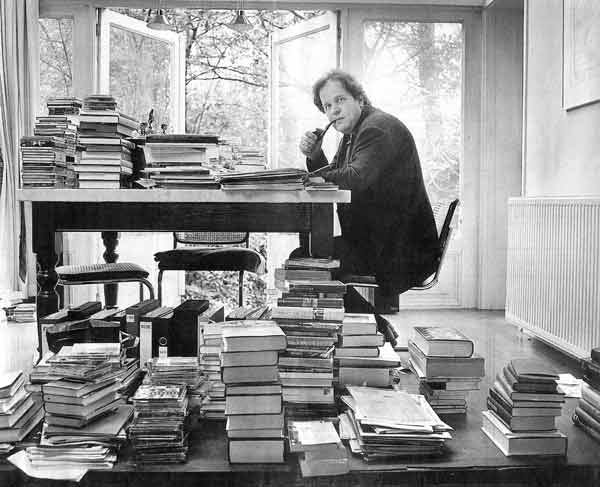

Michael Zeeman - Copyright Bezige Bij

In my first year at the University of Amsterdam I joined Michael Zeeman’s essay writing class. He was a Dutch literary critic, poet, and journalist with his own TV-programme. To me he was an authority, and I am not embarrassed to admit he intimidated me. He was a giant man, with a giant mind and a giant aura. Or at least some sort of energy field around him that magnetized and repulsed at the same time.

I had written a few cultural studies papers during my previous studies at LCF that were pretty much the same as essays. I thought. I wanted to learn more and noticing Zeeman’s name on the roster I ran to the student councillor. I needed permission to attend classes that weren’t part of my faculty (I did this so often that the university eventually granted me a free study path to do what I wanted). I felt a sense of urgency that I had to take this class. At the same time, I was terrified at the thought of having someone of this stature critique my work.

I figured that the word “essay” came from “essayer”, to try or attempt. When I Googled it again just now, to clarify for myself how to approach the different sections I created on Substack, essay, column, or journal, I found a simplified definition, describing an essay as a short piece of writing to convince or inform the reader. Zeeman’s statements were crafted to encourage us to the do the first. Merely inform would not have satisfied him. “Do or not do there is no try.” If there ever was a moment in my life where Yoda’s words applied, it was this. Mr Zeeman didn’t suffer fools lightly and there was no room for trial and error. He expected your best. Continuously.

Writing an essay on a personal experience is a more intimate exercise than for example writing a more academic essay demonstrating critical thinking and contributing, or challenging, paradigms. I have half-written essays on file about anything from womanhood to the cultural appropriation of Roma identity in fashion. No matter how much research I do and how much time I spend crafting my thesis, I always hear Zeeman whispering: No Leonieke, that is not it.

Joan Didion. I know it is a cliché referencing this American author in the context of essay writing, and there definitely seems to be a love and hate camp going on here. But I came late to the party and only properly explored her work two years ago, starting with her memoir “The Year of Magical Thinking”. It moved and mesmerized me. Comparing my words to hers I would have to agree with Mr Zeeman. Not there yet, Leonieke.

I had been introduced to the idea of magical thinking when I had confided in my oncologist the following approach to my cancer: I am going to “pretend” I do not have cancer until every single cell in my body believes it too. A kind of fake it until you make it tactic to get all rogue cells to fall back in line. Reading Didion and thinking back to the last months of my grandfather’s life, when I would go for a five km run and push myself so hard, trying to make a deal with God: If I can run 5 km without having to stop, you won’t let my grandfather die. Magical thinking seems to have a close relationship with the various stages of grief, like denial or bargaining. We want to magic things undone, people undead, opportunities unlost.

Can I take a private conversation with a friend on a delicate topic and turn it into the subject of a magazine column?

“Writers are always selling someone out.” Words of wisdom offered to you by the late Didion. They also resonate with one of Zeeman’s essay statements he gave us to reflect on. His question was whether anything is off limits to a writer. Are we free to take it all? I read an article in a newspaper about a tragic accident. Is it ethical for me to take that event and then incorporate it into a piece of fiction? Can I take a private conversation with a friend on a delicate topic and turn it into the subject of a magazine column? As a writer do I need people’s permission to hijack their personalities, steal parts of their lives?

I took an absolute stance and said no. Nothing is off limits. Everything I write comes from me, my life, and even a hermit like me does not exist in a vacuum. Everyone and all the experiences we share are my material. On Substack I don’t use names but refer to “friend”. My immediate family members are a bit screwed though, as I have only one mum and one dad. I am sure that when my next piece of fiction is done people will recognize parts of themselves, things they have said, little idiosyncrasies that I have borrowed and sprinkled over my characters. I don’t ask for permission now and if anyone is unhappy with it, I doubt I will apologize later. Adopting this position implies that I need to get as I good as I give. It works both ways. Feel free to take me, my life and everything in it and do with it what you will. Make it yours. I might be annoyed though if you do a better job than me or leave me thinking “I wish I had thought to write about that”. But then again, everything has already been written, all the art created, and all the music composed and yet there is nothing stopping us from doing more of it all.

A fellow student in our class took offence and almost burst into tears. When he was younger his brother had been involved in a fatal car accident. At the time he and his family had been living on a large country estate, part of which they shared with a famous Dutch author. The accident and the aftermath, devastating to the family, had popped up in a novel a few years later. The family had felt betrayed. Their private grief was out there for the world to read. To them it didn’t matter if it had been fictionalized, that likely most readers would never know it was inspired by real events, shared so closely with the author.

A few years ago, a millionaire businessman from Dubai asked me to ghost write his autobiography. While discussing terms and conditions he said he wanted to give me the rights to the book. I did not understand this. He said: ‘If you write it, it is your story.’ I said: ‘No, you lived it, it is your story.’ We spent a week together laying the groundwork, but eventually alas it didn’t come to pass. I would have loved to write it, as listening to him talk about his life it read like a bestseller. And probably a Netflix series. A friend of mine said, write it anyway. Use what he told you and run with it. Even though his truth was better than most fictional stories I have consumed, I feel torn. He told me everything openly for the purpose of writing his book, together. Even though he had freely offered me the rights already, using it for a novel (it is too much to cram into a short story) would feel like stealing. Like a lawyer or doctor breaking privilege. Maybe my stance on nothing being off limits to a writer is not so absolute after all.

Zeeman consistently gave me a 7,5 for each of my essays. It did not matter if I wrote it in 3 hours or in three days. It did not matter whether I did research or just used what was already in my head. It did not matter if I had elaborately debated it with friends, family, neighbours or the boy stacking the shelves at the local supermarket or had just written it all down quietly. Each and every damned essay came back with a 7,5 and no red markings, no comments in the margins. After five weeks I worked up the courage to go up to Zeeman during our coffee break. He was standing leaning against the table, which looked odd because he was so tall. He looked at me and said: “Tell me everything”. I ignored that and said: “I have a question. Why do I always get 7,5?”

“Don’t you think it is a bit mediocre?”

He looked at me intently: “Are you pleased with a 7,5?” I was, because he was after all Mr Zeeman the giant literary critic, but I wanted to progress. “Don’t you think it is a bit mediocre?” Ehmm. “I think that you are everything but mediocre. But every time I read your work, I like the flow and I go along with it until at the end, I think, you could have fooled me. But you didn’t. And you also didn’t convince me.’

Ah.

Michael Zeeman died ten years later from a brain tumour. It made think of the way Stephen Fry explained why he doesn’t believe in God.